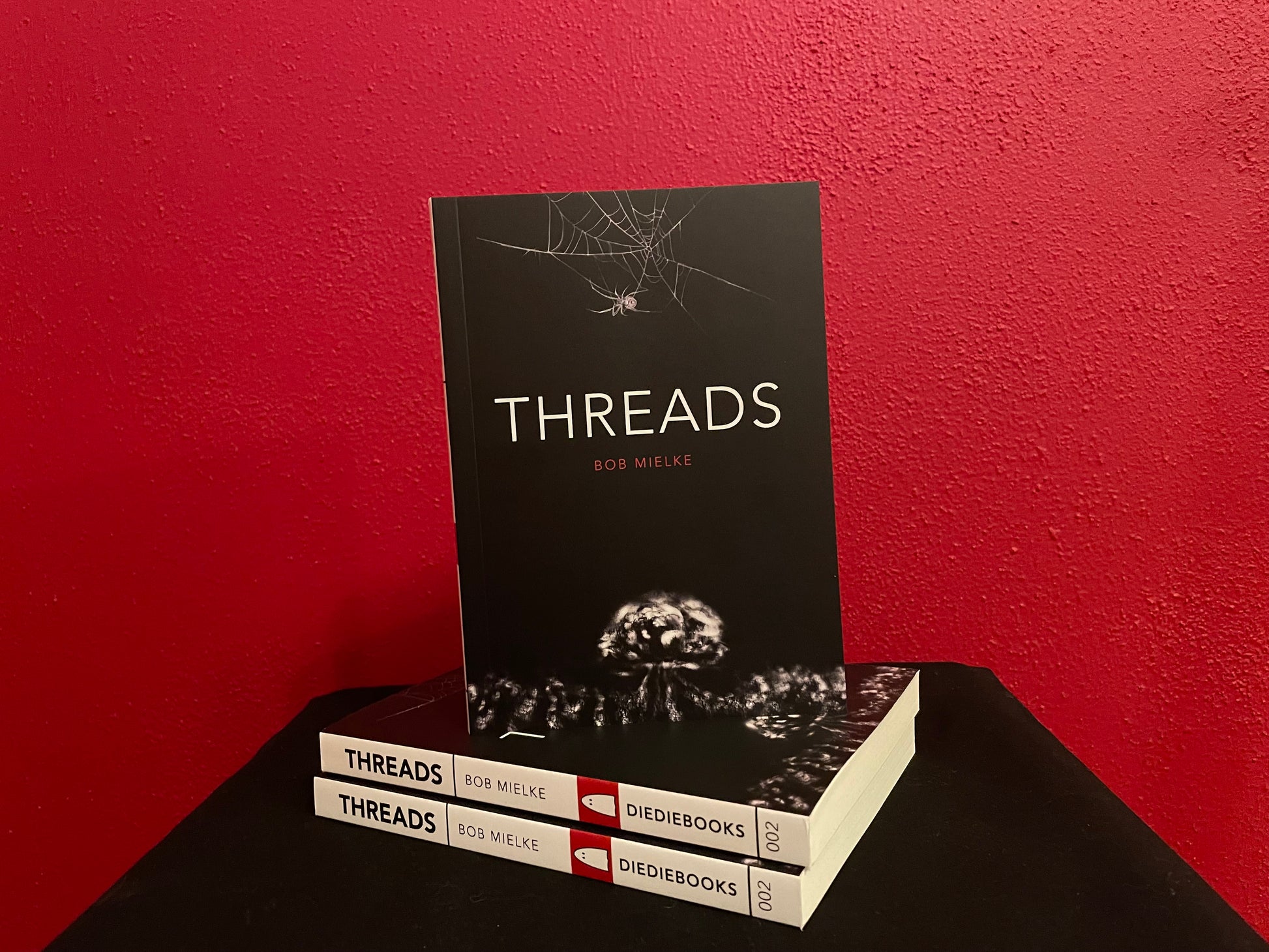

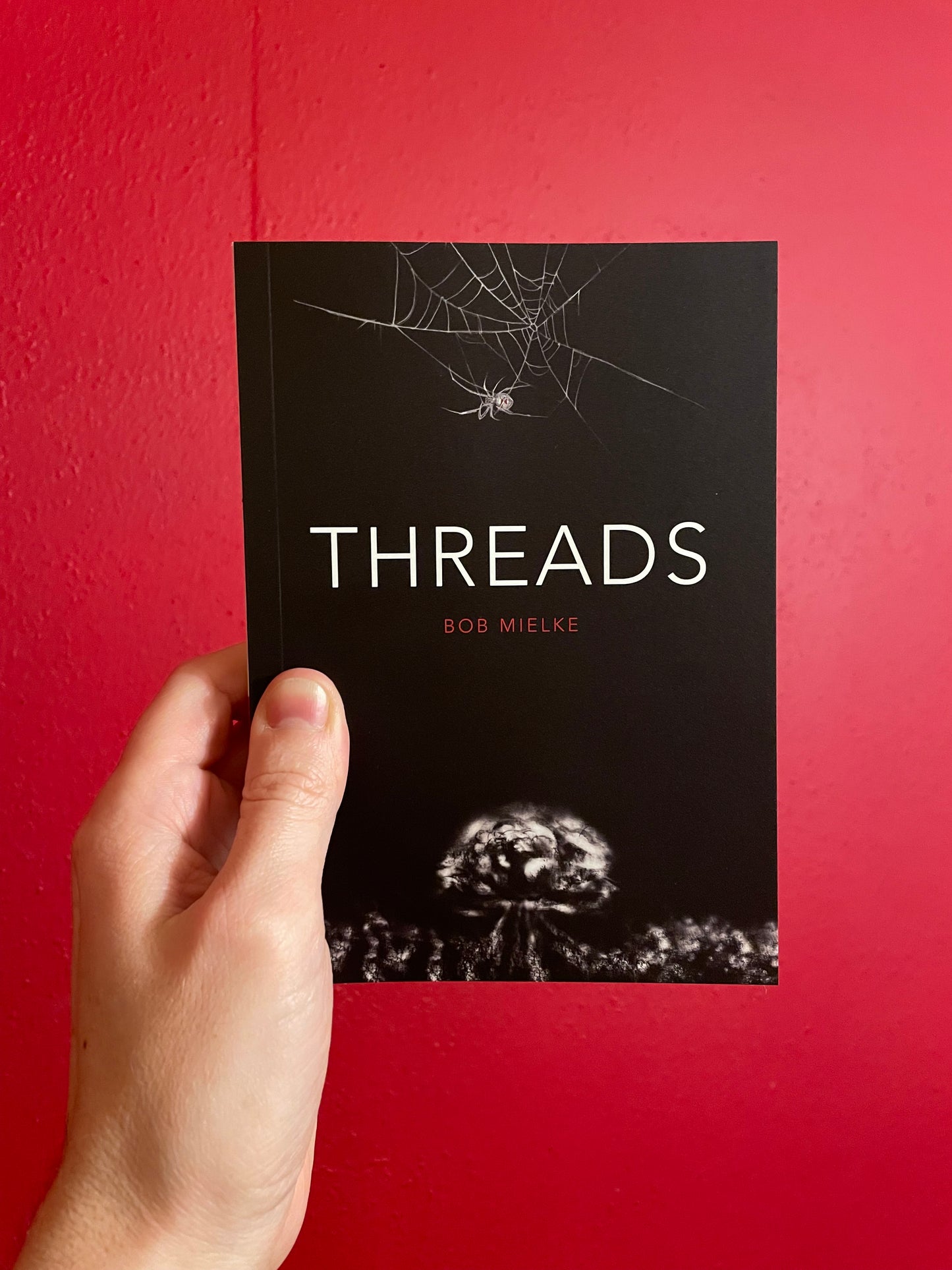

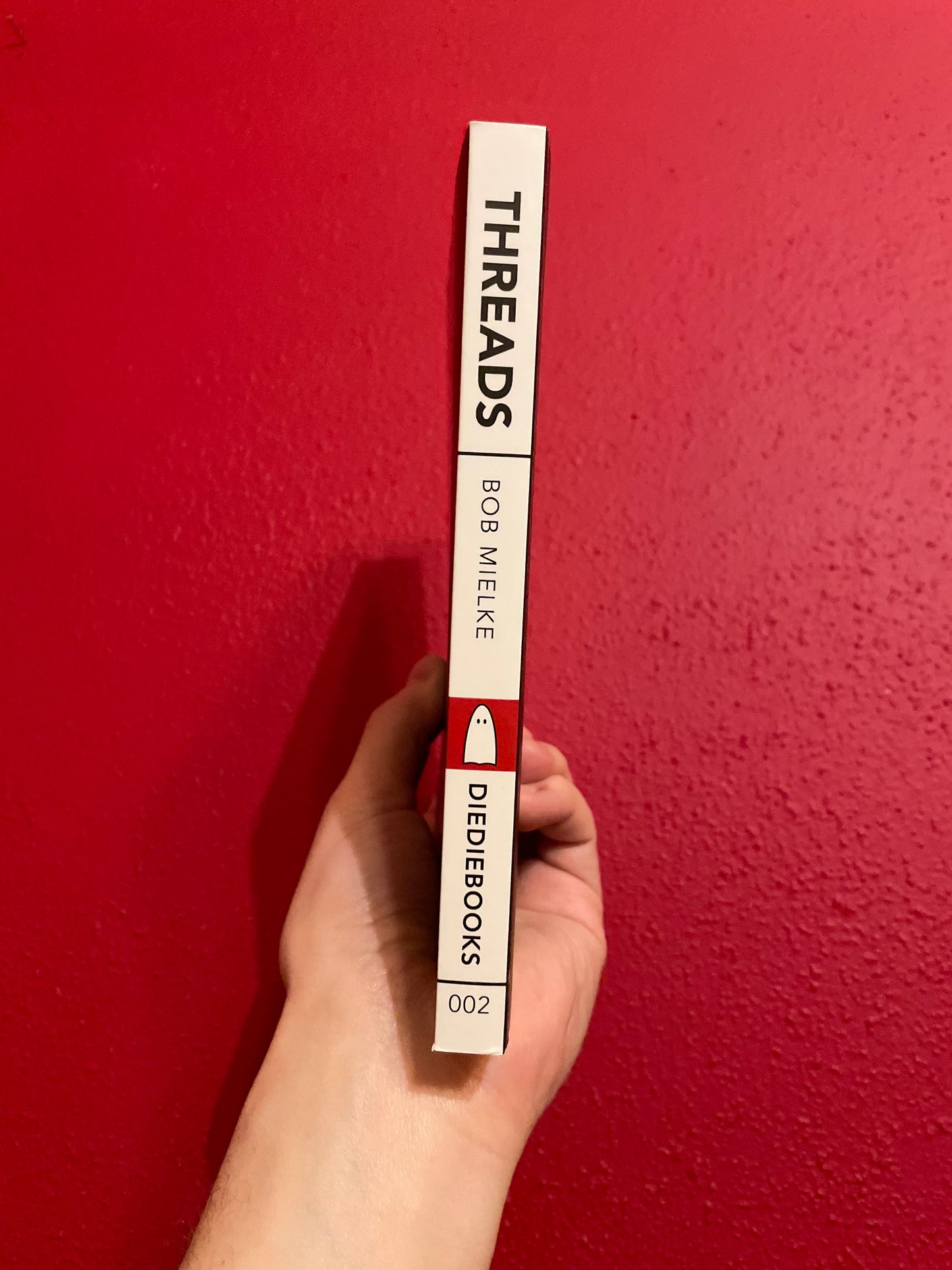

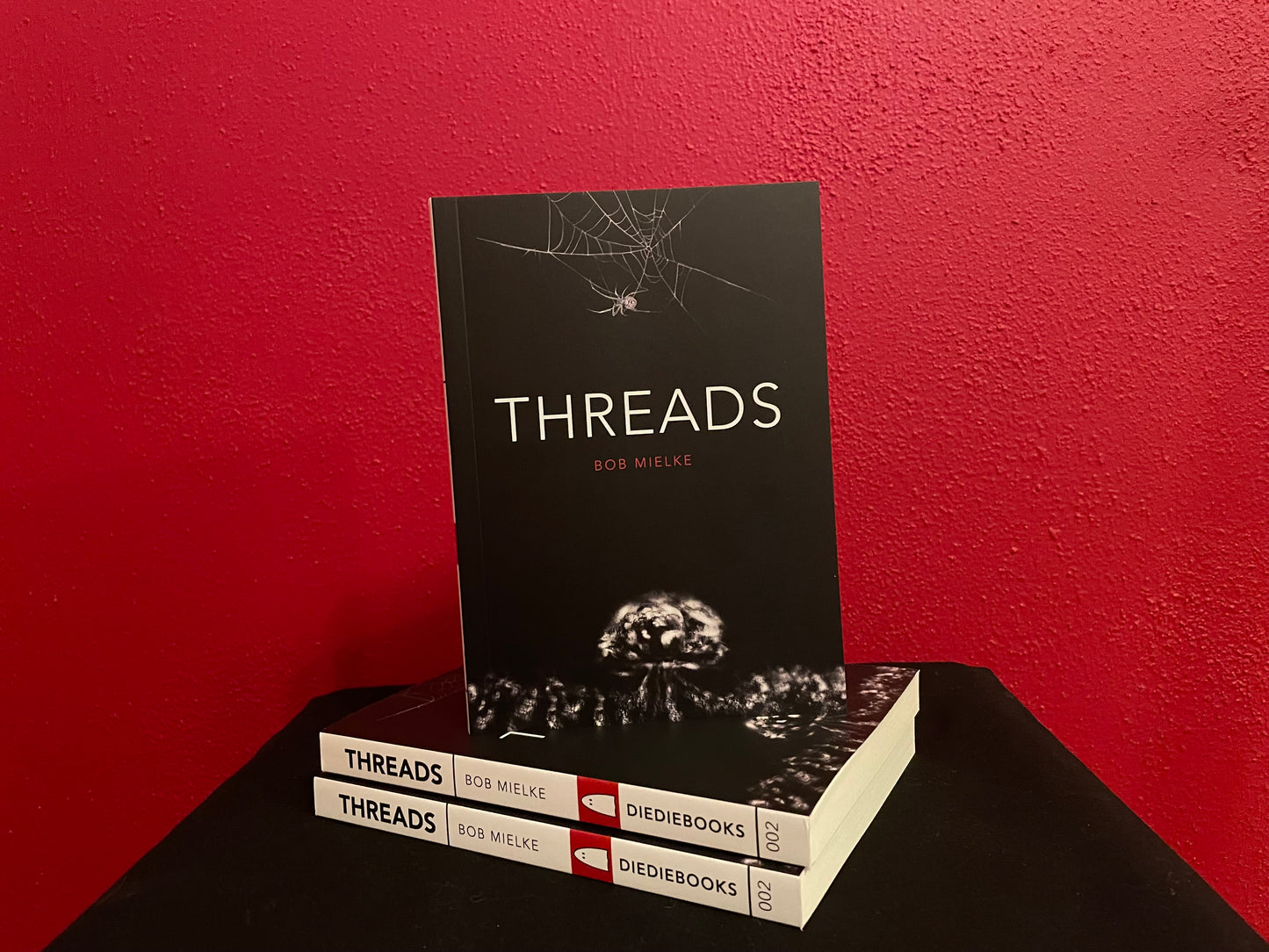

Threads by Bob Mielke

Threads by Bob Mielke

Couldn't load pickup availability

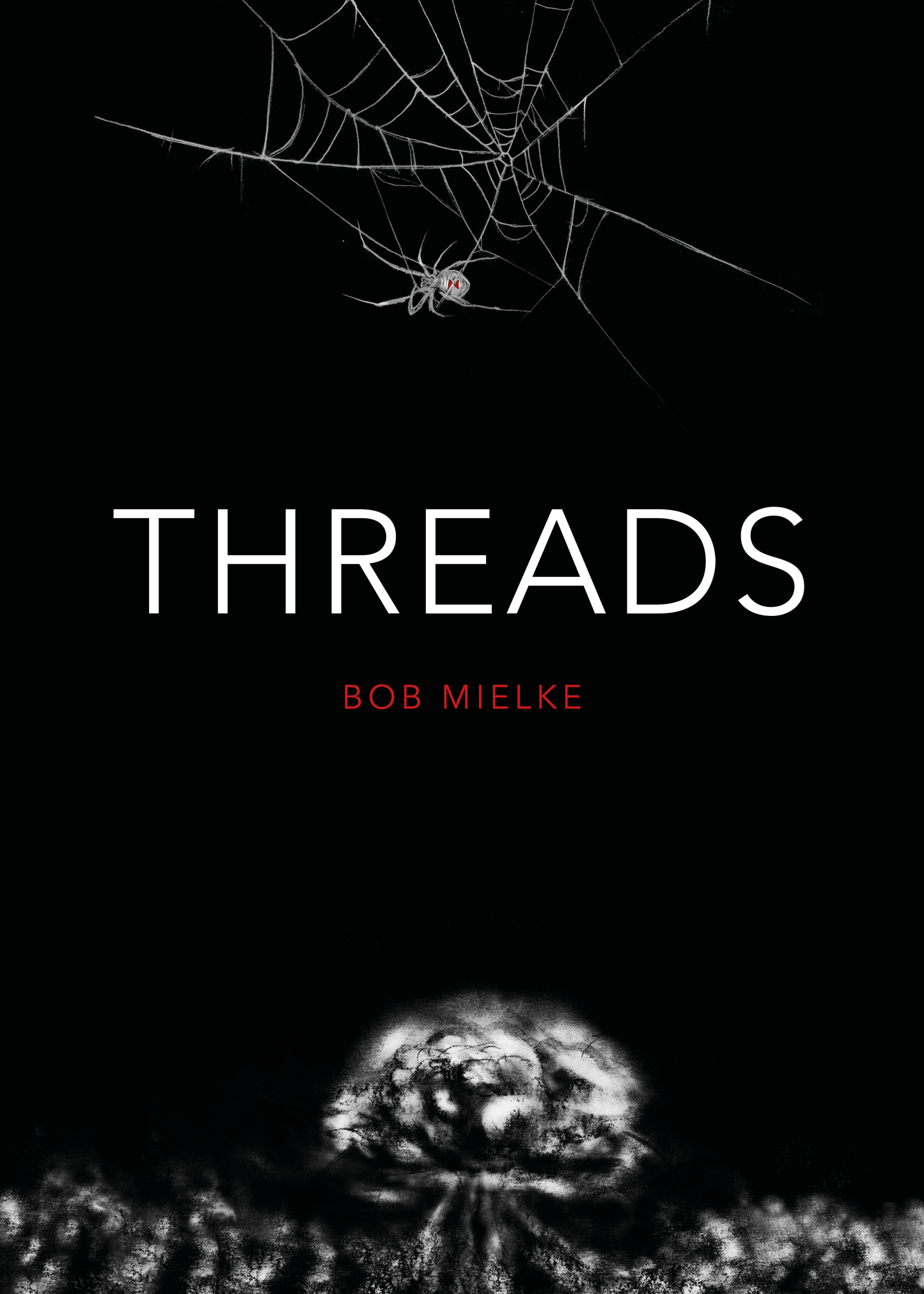

At any moment, our world leaders are just a few nuclear codes away from upending life as we know it. The consequences of that decision are more terrifying than any ghouls that haunt your nightmares. Threads (1984) is a movie that pulls no punches, reveling in the slow-building sense of dread that arises from its nightmarish—and painfully realistic—depiction of the lead-up, destruction, and years-long aftermath of a nuclear attack. Commissioned by the BBC to warn audiences about the dangers of the Cold War, this television film has since been reclaimed and celebrated by horror fans as one of the scariest movies ever made.

Combining decades of nuclear activism and hands-on research at ground-zero sites with a background in film and cultural studies, Bob Mielke examines Threads through the lens of history, pop culture, and horror. Mielke’s impeccable research, sharp analysis, life experience, and gallows humor bring new insight into exactly what makes this film so disturbing—and disturbingly enduring.

Ebook formats

Ebook formats

Ebooks are available in MOBI, EPUB, and PDF formats.

-

— Karen Meagher, star of Threads

"I hope the reader will consider every word Mielke has written in this comprehensive and considered, yet easily accessible, book. It took me right back to the visceral experience and time that was Threads."

-

— Mikita Brottman, author of Meat Is Murder

"You cannot win a nuclear war, but as Mielke explains in this genial and engaging guide, you can definitely enjoy watching one. Although Threads paints a grim portrait of post-nuclear-war Sheffield, Mielke's lively, lucid and cheerful book makes the doom a little less relentless."

Reviews for Threads by Bob Mielke

-

The Pitch KC

Read more"Mielke delivers on his potential by turning over a wildly engaging text but equally singular in perspective—no one else could have written this, and you feel smarter just for having picked up his treatise."

-

Dread Central

Read more"What Mielke accomplishes here is nothing short of remarkable. Lucidly conceived, fastidiously researched, and accessibly written, this is horror as education; horror as illumination."

Excerpt from Threads by Bob Mielke

The Final Final Girl: Threads as Horror Film

Click here to read a sample of the chapter

Scholars of horror films have noted with interest how this genre has a highly permeable relationship with other types of films. Carol Clover in her seminal Men, Women, and Chain Saws shows how an outré rape-revenge film like I Spit On Your Grave (1977) got mainstreamed as a courtroom drama with The Accused (1988) (151). Rick Worland in his genre guide The Horror Film pinpoints the trauma experienced by 1960 audiences who watched Psycho believing it was a crime drama until the shower scene, when it abruptly turned into gothic horror — and arguably the first slasher film.

A somewhat comparable genre permutation is also at work, I would submit, in the rediscovery of apocalyptic nuclear war films as horror films. When they first appeared, these films were perceived as belonging to another genre: the social problem film. Examples of this hardy category include Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner and Black Like Me (for racial issues), The Lost Weekend and Days of Wine and Roses (alcoholism), Gentlemen’s Agreement (anti-semitism), and the more recent Spotlight (priestly pedophilia and sexual abuse).

As previously noted, Nicholas Meyer, the director of The Day After, thought he was making a feature-length Public Service Announcement. And indeed some nuclear war films remain best considered as social problem cinema: obviously Japanese films about the World War II atomic bombings like Shohei Imamura’s Black Rain (1989, not to be confused with the Michael Douglas thriller) which depict the sufferings and social ostracism experienced by hibakusha who have survived the blast. But beyond that, even Stanley Kramer’s On the Beach (1959), which does offer us a nuclear apocalypse and the end of the world as far as humans are concerned, does not really seem to fit the genre of horror beyond the most rudimentary sense that it scares us with its imparted perception of our vulnerable existence in the nuclear age, subject to ready annihilation.

The peculiar status of On the Beach as an apocalyptic non-horror nuclear film stems in large part from its quaintly chaste depiction of the effects of a nuclear exchange. When Gregory Peck’s sub surfaces in San Francisco Bay, we see a deserted but not bombed town where everyone went indoors conveniently to die of radiation sickness. No corpses, nothing for the makeup people to do: a sop to the tender liberal audience the film was made for whose imaginations would provide the distressing imagery. No other nuclear apocalypse on film would wear these sorts of kid gloves.

But overall, it makes abundant sense to view apocalyptic nuclear war films in general, and Threads in particular, as horror films — and we shall be quite busy in this chapter counting all the ways that horror is the best genre description to be applied to Mick Jackson’s Blu-ray nasty.

Rick Worland makes the obvious and necessary point that a horror film “is a movie that aims foremost to scare us.” Viewed from this perspective, nuclear weapons and horror films are virtually doppelgängers. From its inception, the bomb was a psychological terror weapon. More people died in the “conventional” (non-nuclear) fire-bombings of Tokyo on a strategically successful night for the allies in the spring of 1945 than perished initially in either Hiroshima or Nagasaki. The psychological impact of a nuclear weapon derives from its concentrated lethality: one device as opposed to 20,000 tons of explosives delivered in scads of bombs.

And, of course, deterrence theory derives from this fear. In a travel magazine article about the nuclear weapons laboratory at Los Alamos that a student showed me, a weaponeer explained to the reporter that his job was like the witch in a Grimm’s fairy tale: “to scare you into being good.” Stanley Kubrick’s initial title for Dr. Strangelove was The Delicate Balance of Terror, riffing on the actual notion of a “balance of terror” in nuclear strategy predicated upon “mutual assured destruction” (aptly given MAD as an acronym).

When I teach classes in horror literature or film, I always find it helpful to break down further how we are scared and why we are frightened. Stephen King’s tripartite classification for me is a useful place to start:

The 3 types of terror: The Gross-out: the sight of a severed head tumbling down a flight of stairs, it's when the lights go out and something green and slimy splatters against your arm. The Horror: the unnatural, spiders the size of bears, the dead waking up and walking around, it's when the lights go out and something with claws grabs you by the arm. And the last and worse one: Terror, when you come home and notice everything you own had been taken away and replaced by an exact substitute. It's when the lights go out and you feel something behind you, you hear it, you feel its breath against your ear, but when you turn around, there's nothing there… (Facebook post 1/13/2014 summarizing his horror exegesis in Danse Macabre)

As we might expect from a master of horror, he covers all the bases here — although as a former English teacher King ought to know better than to make terror both an overarching category and the third subcategory of his variations. But all one need do here to fully understand his point in a more explicitly psychological way is to consider these three types as Kristevan abjection, Freudian phobias, and Freud’s concept of the Uncanny. Let’s unpack these ideas and see how they can all be abundantly found in Threads...

Bob Mielke has been a scholar and activist in the field of nuclear research for over four decades. He is a Professor of English at Truman State University, teaching literature, film, and cultural studies. His other publications include works of poetry, playwriting, music criticism, and a co-authored work of photojournalism on atomic imagery.