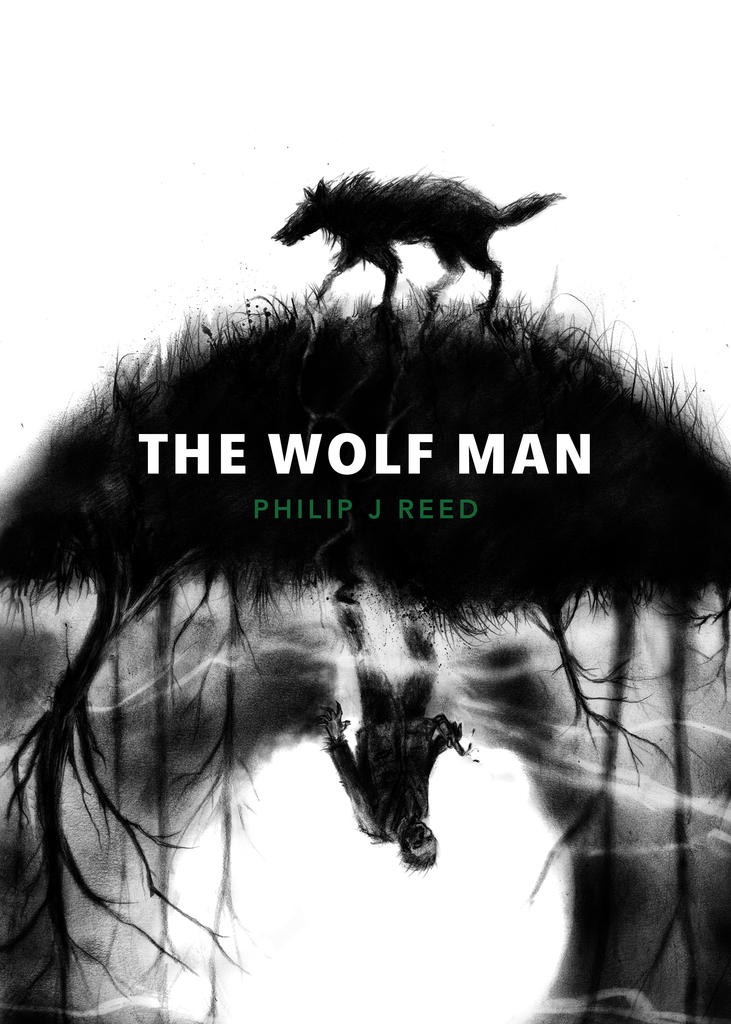

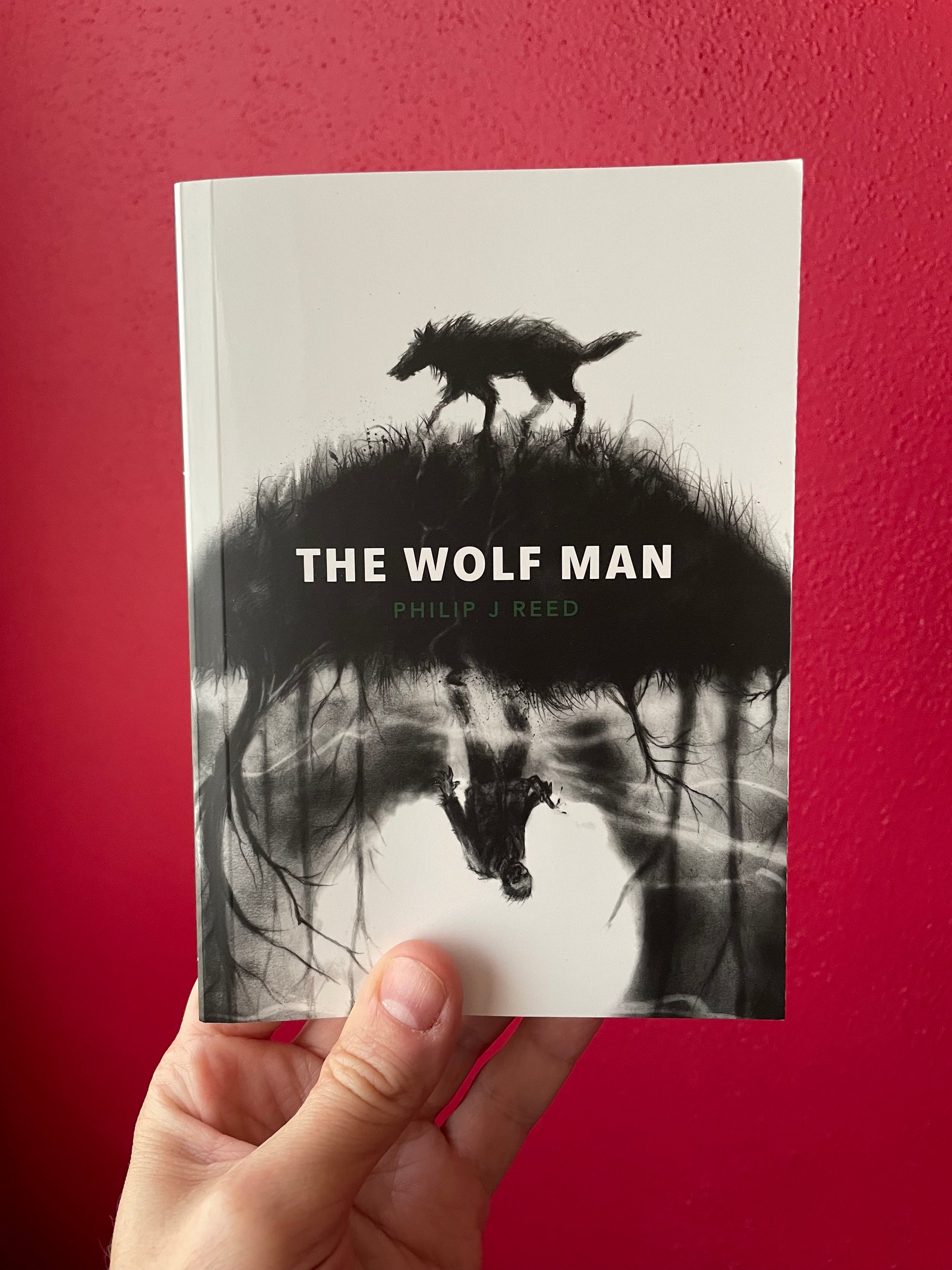

The Wolf Man by Philip J Reed

The Wolf Man by Philip J Reed

Couldn't load pickup availability

1941's The Wolf Man endures as a masterpiece of the classic Universal horror films, but this deeply felt work also offers a unique insight into the complex psychology of its lead actor. Lon Chaney Jr. rarely opened up in interviews and, when he did, the information he provided about himself was vague and contradictory. This was perhaps intentional; like the character he played in The Wolf Man, Chaney had a monstrous side that he did his best to keep hidden.

Pop culture writer, humorist, and horror cinephile Philip J Reed analyzes the iconic film, using it and a collection of interviews, press materials, and biographical sources as a basis for discovering who Chaney really was when the cameras turned off and night fell. Chaney's work on screen provides valuable insight into his real-life struggles with alcoholism, violence, depression, and a tortured relationship with his celebrated, even more monstrous father.

The Wolf Man is an effective work of lingering horror. The story of its lead actor might be even more haunting.

Ebook formats

Ebook formats

Ebooks are available in MOBI, EPUB, and PDF.

-

Dread Central

Read more"I’d go so far as to call it a masterpiece, accountable for one of the most visceral, moving reactions I’ve had to a piece of writing in some time."

EXCERPT FROM THE WOLFMAN BY PHILIP J REED

The Sign of the Werewolf

Read an excerpt from the chapter

Many actors could have played Larry Talbot, but Chaney imbues the character with a specific layer of depth that others might not have been able to match—and probably wouldn’t have thought to try matching. In his scenes with [Claude] Rains, there’s a strange humility about him.

Rains was only 17 years older than Chaney, and the gap seems to be even narrower when looking at them physically. Further, since Rains is substantially smaller than Chaney, it makes the father-son relationship even less immediately apparent.

The two could have played friends or brothers easily, but Chaney’s life experiences inform—deliberately or not—how he approaches and interacts with Rains. This not only sells them as father and son, but establishes one very particular kind of relationship between father and son. It’s one that the script doesn’t need, but the film benefits from it immensely. It seems to be saying something, even when it is not deliberately saying anything.

The fact that Chaney’s life experiences inform his performance is even more apparent in the next major scene, during which Larry visits Charles Conliffe Antiques, a store located a short distance away from Talbot Castle.

While testing his father’s telescope, Larry spies Gwen Conliffe (Evelyn Ankers) trying on jewelry in her room above the shop. It’s worth noting how easily this moment with the telescope could be read as either cute or sinister. The film wants us to see it as harmless, but we have room to see it both ways, and that ambiguity is entirely due to Chaney’s portrayal.

Larry peers at the woman, who is completely unaware that a telescope is pointed into her room. He finds her attractive and makes a point of stopping by the antique shop later, where he finds her working. He asks about a pair of gold earrings, shaped like half-moons, which she had privately worn in her room earlier. She’s caught off guard. He half-heartedly claims to be psychic.

Many leading men in Classical Hollywood—whatever our more progressive viewpoints might be today—could make every element of this sequence seem charming, playful, or even sexy. In contrast, many talented character actors could make every element seem worrying, creepy, and unnerving.

When a man spies on a woman and then makes advances toward her, there are two obvious extremes that the movie could then explore. Chaney’s halting, uncertain performance causes it to land at the precise midpoint between those extremes, lending it a remarkable degree of emotional ambiguity.

When I first watched this film with my friend, this scene marked the moment at which I knew I was in for something more than a silly monster movie. Had you asked me then why I had that feeling, I would not have been able to articulate it; I doubt that I could have even understood it. Now, it’s a little more clear to me: By refusing to fix itself at either extreme, the sequence feels more human. We all operate between extremes. We live our lives between extremes. Extremes make for excellent cinematic shorthand, but rarely do they make for good characterization.

Was this ambiguity an intentional or unintentional part of The Wolf Man? Whether it was deliberate or not, the end product benefits from vagueness.

We will learn definitively that Larry is not a bad person, but we don’t know that yet. He approaches a woman who has never met him and uses what he knows about her to keep her off guard. What are his motives, exactly? Was it genuine happenstance that he spotted Gwen through the telescope, or was he the type of person who might have scanned around for pretty ladies anyway? Is he curious about who she really is, or would he pursue her no matter what? Is he willing to make a friend, or is he intent on a different kind of relationship?

It’s hard to know, because Chaney doesn’t play the scene as either suave or sinister. Personally, I think it’s more that he can’t play the scene as either suave or sinister; he wasn’t capable of pulling off the former, and the script didn’t allow for the latter.

Larry’s tragedy is so all-encompassing that it extends to his casting, with audiences unsure how seriously they can even take the romantic fumblings of this awkward, uneasy man. The film wants us to take him seriously, but Chaney’s own uncertainty prevents us from doing so.

What we get is a shockingly sincere portrait of a man so uncomfortable in his own skin that he can’t so much as flirt with the shopkeeper without stumbling over himself and mixing his own messages. He wants to woo her, but he doesn’t know how. He wants to be charming, but he comes off as bumbling. He wants to be approachable, but he presents himself as off-putting.

All of this could work—and easily so—if the film wanted this to be the case, but Larry isn’t written as an awkward character, and the scene is not played for comedy; it’s played straight. Humphrey Bogart could walk into any room and charm whatever information he’s after out of the sexy blonde without having to do more than light a cigarette, but Larry seems never to have mastered even basic social interactions at any point in his life.

When I first watched the film, I couldn’t have known whether that was the filmmaker’s intention, the writer’s intention, the actor’s intention, or some combination of the above. Now, I’m pretty sure that it’s none of the above.

Larry is meant to be flirting effectively with Gwen, but Chaney doesn’t know how to do that, so he can’t. The end result is that when Gwen repeatedly turns down his offer for a date that night, it doesn’t feel like the playful back-and-forth it’s meant to be; instead, it feels like a schlub getting shot down.

In short, when Gwen says “no” to Larry, we are supposed to hear “yes.” But when Ankers says “no” to Chaney, we can only hear—at best—“no, thank you.”

Let’s be clear: This is not what the film intends. I love The Wolf Man, but I won’t pretend that it’s smarter, more complicated, or more clever than it actually is. What we get here, however, is superior to the film’s intentions.

It feels real—and is real—in a way that ultimately works to The Wolf Man’s credit. Its eventual visual horrors might not carry much weight 80-odd years later, but the very human moments that the film managed to capture are every bit as relatable and insightful as they ever were, and every one of them comes courtesy of Chaney.

Even Larry’s purchase of a cane feels less like the plot point that the movie needs it to be and more like the act of a desperate man who has struck out and needs, in some way, to justify the fact that he entered the shop at all.

The cane that he selects has a silver handle shaped like a wolf and is marked with a pentagram which, according to local legend, is the sign of the werewolf.

“That’s a human being who, at certain times of the year, changes into a wolf,” Gwen exposits.

“You mean runs around on all fours and bites and snaps and bays at the moon?” Larry asks.

“Even worse than that sometimes,” she says, reminding us that monsters aren’t monsters strictly because of how they look; monsters are monsters because of what they do.

We are also, of course, reminded of the fact that monstrous behavior is not innate to any particular kind of person; all of us, in theory, are capable of it. A man may not be a monster, but that man may always become a monster.

Philip J Reed was an award-winning author and critic who lived in Denver, Colorado. He has written about video games for outlets including Nintendo Life and TripleJump, and is the author of a full-length book about the making and legacy of Resident Evil. Reed passed away in July 2022, and much of his writing remains available on the website he managed, Noiseless Chatter.